Samuel Beckett.

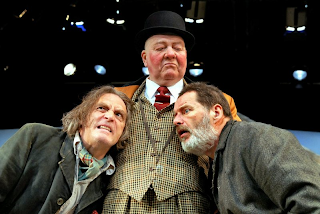

Waiting for Godot: A Tragicomedy in Two Acts.

New York: Grove Press, Inc. 1954. [Now Grove/Atlantic: ISBN 978-0-8021-4442-3.]

I am struggling to begin this review. But, before I do, WfG gets from me a solid ★★★★★ out of ☆☆☆☆☆. In fact, it was so good that as soon as I finished it the first time, I promptly re-read it.

My struggle is between being too glib: "This is a brilliant metaphor for the condition our human condition has conditioned us to unconditionally accept" — to being too dismissive, such as was expressed by a co-worker who, upon learning I was reading Godot, said "I watched it on TV. It was great! A great play about nothing." Now I suspect that because he reacted to 'nothing' so strongly that his unconscious did not in anyway find it to be empty.

And so it, is, that despite an ostensible appearance that it is about nothing, nothing is further from the truth. WfG is definitely not about nothing. The metaphors are nearly endless, from the simple ones such as the too small boots pinching the feet — constricted understanding hobbles psychological/emotional movement. Beckett even extends that to include putting on another's boots in the hopes of acquiring the ability to walk with less discomfort, metaphor for putting on another's ideas.

I haven't gone onto the web to search for the likely endless reams of ideas this play has generated. Nor do I want to do a review of the play, as such. Instead I would like to briefly concentrate on the character Lucky. [Note: I will discuss this role in some detail, so if you want to be surprised by Lucky in the play, do not read on before reading the play.]

Lucky comes onto the stage with a noose around his neck carrying a collection of stuff. The end of the rope extends out of sight, off stage, making Pozzo, Lucky's master, initially invisible. (Is that the smallest of hints of Adam Smith's Invisible Glove?) Pozzo controls Lucky with the use of the noose, via jerks (Lucky has open sores from it), and with a whip and short, usually one word, commands such as the On! and Back! that introduce the pair. Later, Pozzo wants to put Lucky's intellectual prowess, specifically his ability to think, on display for Estragon and Vladimir, the pair waiting for Godot:

POZZO: Stand back! (Vladimir and Estragon move away from Lucky. Pozzo jerks the rope. Lucky looks at Pozzo.) Think, pig! (Pause. Lucky begins to dance.) Stop! (Lucky stops.) Forward! (Lucky advances.) Stop! (Lucky stops.) Think![I blogged this section more extensively as part of a peculiar fushigi @ Godot, Ballet, Pocket Watch & Alice.]

(Silence.)

LUCKY: On the other hand with regard to—

This has particular resonance for me because of a recent employee motivational propaganda campaign I (and at least several thousands of others) were subjected to. It was comprised of a series of 3 posters and their electronic facsimile being festooned across the offices. The posters were comprised of two parts. The top half was a single word, a command: Say, Stay, Strive. The balance were terse reasons for obeying the command, for the last two, and what to say for the first one.

Less specifically, the extended thinking that Lucky expresses is, of course, a perfect metaphor for what passes for thinking through the news media and many official journals: a huge pile of impressive sounding phrases that at best hide the truth but at worst promulgate false truths and ideology. And all co-mingled with a curious obsession about sports. [I wonder if Beckett was influenced by some of George Orwell's pointed criticism of the media and much intellectual thought, such as he delineated in Homage to Catalonia? Wikipedia does not reference such a connection.]

But why does Lucky stay with the physically and verbally abusive Pozzo? He is, ostensibly, a free man. Pozzo even ascribes to him freedom. Well, the answer is an interesting one, and reminds me of the current batch of presidential candidates who blame the poor for being poor because if they didn't want to be poor they could work themselves out of it. Here's Pozzo's reasoning for Lucky's enslavement to him:

POZZO: Ah! Why couldn't you say so before? Why he doesn't make himself comfortable? Let's try and get this clear. Has he not the right to? Certainly he has. It follows that he doesn't want to. There's reasoning for you. And why doesn't he want to? (Pause.) Gentlemen, the reason is this.Interesting. Lucky has enslaved himself in order to appease his master, to be liked enough to be seen as worthy by Pozzo.

VLADIMIR: (to Estragon). Make a note of this.

POZZO: He wants to impress me, so that I'll keep him.

ESTRAGON: What?

POZZO: Perhaps I haven't got it quite right. He wants to mollify me, so that I'll give up the idea of parting with him. No, that's not exactly it either.

VLADIMIR: You want to get rid of him?

POZZO: He wants to cod me, but he won't.

VLADIMIR: You want to get rid of him?

POZZO: He imagines that when I see how well he carries I'll be tempted to keep him on in that capacity.

ESTRAGON: You've had enough of him?

POZZO: In reality he carries like a pig. It's not his job.

VLADIMIR: You want to get rid of him?

POZZO: He imagines that when I see him indefatigable I'll regret my decision. Such is his miserable scheme. As though I were short of slaves! (All three look at Lucky.) Atlas, son of Jupiter! (Silence.) Well, that's that, I think. Anything else?

(Vaporizer.)

VLADIMIR: You want to get rid of him?

POZZO: Remark that I might just as well have been in his shoes and he in mine. If chance had not willed otherwise. To each one his due.

VLADIMIR: You waagerrim?

POZZO: I beg your pardon?

VLADIMIR: You want to get rid of him?

POZZO: I do. But instead of driving him away as I might have done, I mean instead of simply kicking him out on his arse, in the goodness of my heart I am bringing him to the fair, where I hope to get a good price for him. The truth is you can't drive such creatures away. The best thing would be to kill them.

(Lucky weeps.)

ESTRAGON: He's crying!

POZZO: Old dogs have more dignity. (He proffers his handkerchief to Estragon.) Comfort him, since you pity him. (Estragon hesitates.) Come on. (Estragon takes the handkerchief.) Wipe away his tears, he'll feel less forsaken.

(Estragon hesitates.)

VLADIMIR: Here, give it to me, I'll do it.

(Estragon refuses to give the handkerchief.)

(Childish gestures.)

POZZO: Make haste, before he stops. (Estragon approaches Lucky and makes to wipe his eyes. Lucky kicks him violently in the shins. Estragon drops the handkerchief, recoils, staggers about the stage howling with pain.) Hanky!

(Lucky puts down bag and basket, picks up handkerchief and gives it to Pozzo, goes back to his place, picks up bag and basket.)

ESTRAGON: Oh the swine! (He pulls up the leg of his trousers.) He's crippled me!

POZZO: I told you he didn't like strangers.

So why did Lucky kick Estragon in the shins? As I have been thinking about this, it struck me that Lucky's behaviour corresponds exactly with those who have fully submitted to their lot in life. My first realization of this tickled out from Noam Chomsky's reference to the 'benevolence' expressed by industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to 'his' workers in 1896:

These are the fruits of the fierce corporate campaign undertaken as soon as American workers finally won the right to organize in the mid-1930s, after long years of bitter struggle and violent repression unmatched in the industrial world. Perhaps we may even return to the days when the admired philanthropist Andrew Carnegie could preach the virtues of "honest, industrious, self-denying poverty" to the victims of the great depression of 1896, shortly after he had brutally crushed the steel workers union at Homestead, while announcing that the defeated workers had sent him a wire saying, "Kind master, tell us what you wish us to do and we will do it for you." It was because he knew "how sweet and happy and pure the home of honest poverty is" that Carnegie sympathized with the rich, he explained, meanwhile sharing their grim fate in his lavishly appointed mansions fn37 (37. Sexton, Patricia Cayo. The War on Labor and the Left Westview 1991, p83f.)Eventually, the people brutalized recognize the futility of fighting it, and so beat anyone who might offer them hope as being trouble makers or a threat to the status quo. Social critic and comic Bill Maher makes frequent reference to the American labourer who descries as a kind of evil the benefits European workers get in terms of time off, health, paternal benefits, etc. instead of struggling to achieve them for themselves.

So a well-ordered society should run, according to the "vile maxim of the masters." (Year 501: The Conquest Continues, pg. 56-7).

Similarly, in the movie Guess Who's Coming for Dinner the parents actively dissuade the interracial couple because there would be trouble for the couple and their parents, too. Freedom roped off with fear.

Lucky is Estragon and Vladimir. Lucky is enslaved to Pozzo by choice — more specifically having chosen willingly or not to accept the lack of choice — not the rope. Estragon and Vladimir are enslaved to the hope of Godot providing them their direction in life.

The metaphors are obvious: we make our choices to remain as we are, whether we are societally successful or not, by accepting the situation we find ourselves in by submitting to choices others have made for us, then hoping that abandoning our Selves to those seen or unseen others will bring us succour.

The challenge, here, is twofold. The courage to see things exactly as they are within ourselves and in the society, and the wisdom to know what can and cannot be changed. I have no idea how either of these things are done.

This play is endlessly rich in meaning. I would now like to see it, and to produce an amateur production of it — or perhaps a reading. Hmmmm.

No comments:

Post a Comment